Last week we looked at how the stack works and how stack frames are

built during function prologues. Now it’s time to look at the inverse process

as stack frames are destroyed in function epilogues. Let’s bring back our

friend add.c:

1 | int add(int a, int b) |

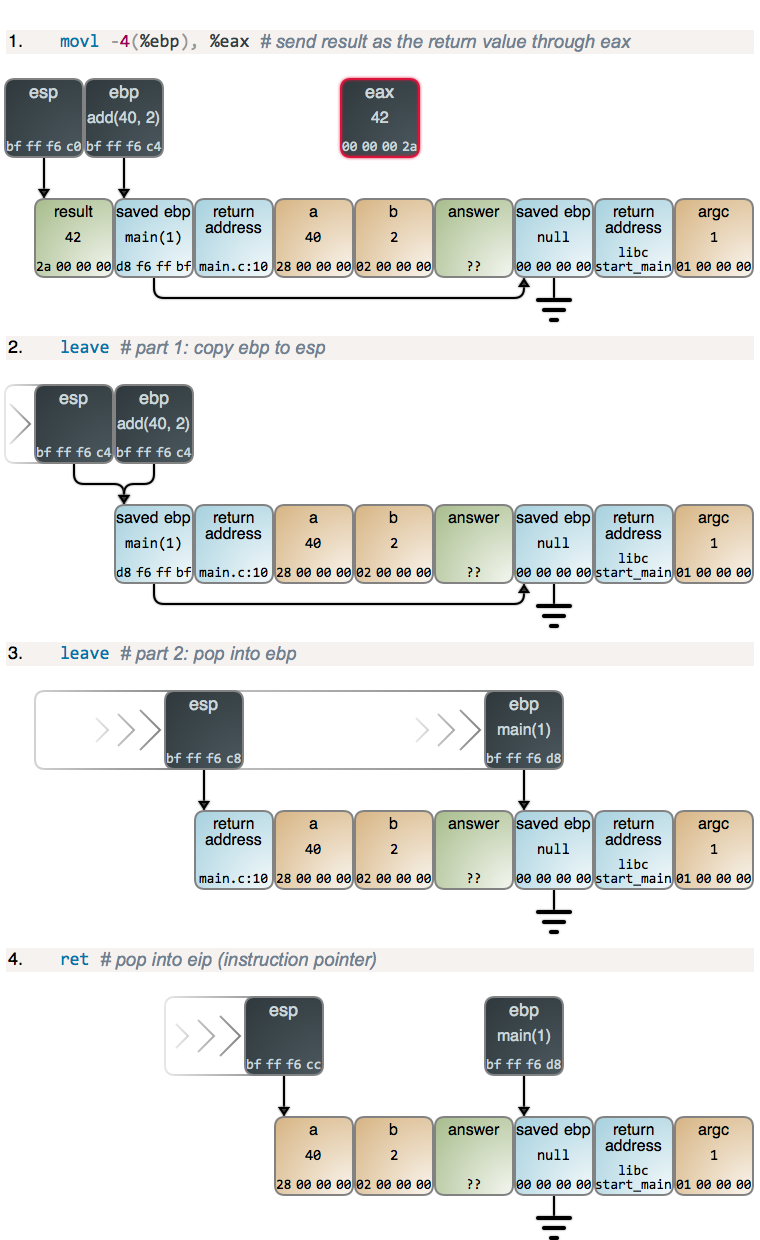

We’re executing line 4, right after the assignment of a + b into result. This is

what happens:

The first instruction is redundant and a little silly because we know eax is

already equal to result, but this is what you get with optimization turned

off. The leave instruction then runs, doing two tasks for the price of one: it

resets esp to point to the start of the current stack frame, and then restores

the saved ebp value. These two operations are logically distinct and thus are

broken up in the diagram, but they happen atomically if you’re tracing with

a debugger.

After leave runs the previous stack frame is restored. The only vestige of the

call to add is the return address on top of the stack. It contains the address

of the instruction in main that must run after add is done. The ret

instruction takes care of it: it pops the return address into the eip

register, which points to the next instruction to be executed. The program has

now returned to main, which resumes:

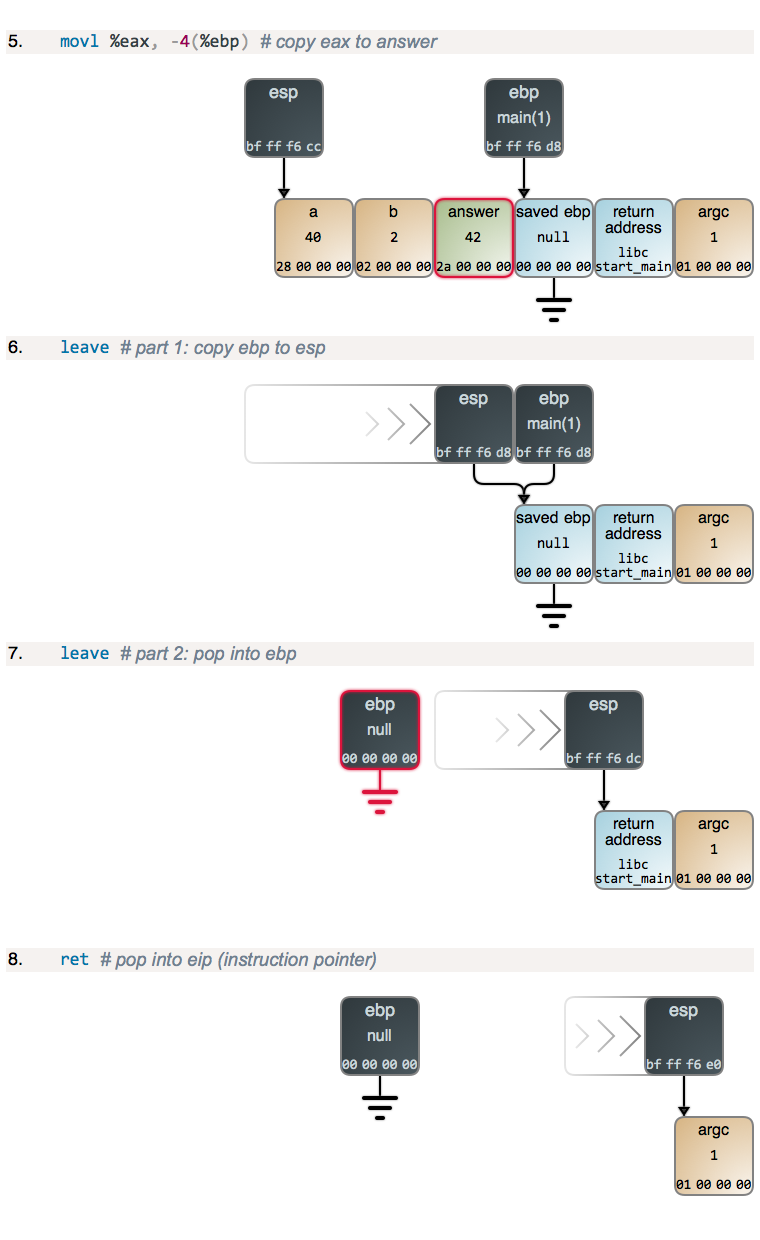

main copies the return value from add into local variable answer and then

runs its own epilogue, which is identical to any other. Again the only

peculiarity in main is that the saved ebp is null, since it is the first stack

frame in our code. In the last step, execution has been returned to the

C runtime (libc), which will exit to the operating system. Here’s a diagram

with the full return sequence for those

who need it.

You now have an excellent grasp of how the stack operates, so let’s have some fun and look at one of the most infamous hacks of all time: exploiting the stack buffer overflow. Here is a vulnerable program:

1 | void doRead() |

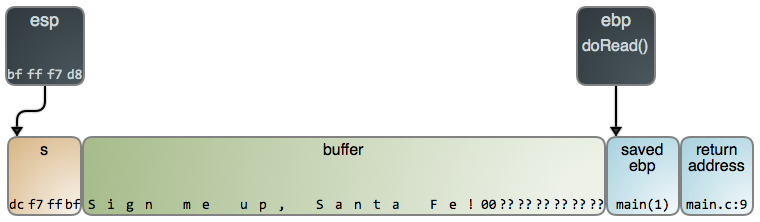

The code above uses gets to read from

standard input. gets keeps reading until it encounters a newline or end of

file. Here’s what the stack looks like after a string has been read:

The problem here is that gets is unaware of buffer's size: it will blithely

keep reading input and stuffing data into the stack beyond buffer,

obliterating the saved ebp value, return address, and whatever else is below.

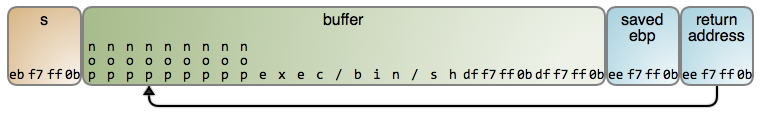

To exploit this behavior, attackers craft a precise payload and feed it into the

program. This is what the stack looks like during an attack, after the call to

gets:

The basic idea is to provide malicious assembly code to be executed and overwrite the return address on the stack to point to that code. It is a bit like a virus invading a cell, subverting it, and introducing some RNA to further its goals.

And like a virus, the exploit’s payload has many notable features. It starts

with several nop instructions to increase the odds of successful exploitation.

This is because the return address is absolute and must be guessed, since

attackers don’t know exactly where in the stack their code will be stored. But

as long as they land on a nop, the exploit works: the processor will execute

the nops until it hits the instructions that do work.

The exec /bin/sh symbolizes raw assembly instructions that execute a shell

(imagine for example that the vulnerability is in a networked program, so the

exploit might provide shell access to the system). The idea of feeding raw

assembly to a program expecting a command or user input is shocking at first,

but that’s part of what makes security research so fun and mind-expanding. To

give you an idea of how weird things get, sometimes the vulnerable program calls

tolower or toupper on its inputs, forcing attackers to write assembly

instructions whose bytes do not fall into the range of upper- or lower-case

ascii letters.

Finally, attackers repeat the guessed return address several times, again to tip the odds ever in their favor. By starting on a 4-byte boundary and providing multiple repeats, they are more likely to overwrite the original return address on the stack.

Thankfully, modern operating systems have a host of protections against buffer overflows, including non-executable stacks and stack canaries. The “canary” name comes from the canary in a coal mine expression, an addition to computer science’s rich vocabulary. In the words of Steve McConnell:

Computer science has some of the most colorful language of any field. In what other field can you walk into a sterile room, carefully controlled at 68°F, and find viruses, Trojan horses, worms, bugs, bombs, crashes, flames, twisted sex changers, and fatal errors?

At any rate, here’s what a stack canary looks like:

Canaries are implemented by the compiler. For example, GCC’s stack-protector option causes canaries to be used in any function that is potentially vulnerable. The function prologue loads a magic value into the canary location, and the epilogue makes sure the value is intact. If it’s not, a buffer overflow (or bug) likely happened and the program is aborted via __stack_chk_fail. Due to their strategic location on the stack, canaries make the exploitation of stack buffer overflows much harder.

This finishes our journey within the depths of the stack. We don’t want to delve too greedily and too deep. Next week we’ll go up a notch in abstraction to take a good look at recursion, tail calls and other tidbits, probably using Google’s V8. To end this epilogue and prologue talk, I’ll close with a cherished quote inscribed on a monument in the American National Archives:

Comments