Here’s a question: in the time it takes you to read this sentence, has your OS been running? Or was it only your browser? Or were they perhaps both idle, just waiting for you to do something already?

These questions are simple but they cut through the essence of how software works. To answer them accurately we need a good mental model of OS behavior, which in turn informs performance, security, and troubleshooting decisions. We’ll build such a model in this post series using Linux as the primary OS, with guest appearances by OS X and Windows. I’ll link to the Linux kernel sources for those who want to delve deeper.

The fundamental axiom here is that at any given moment, exactly one task is active on a CPU. The task is normally a program, like your browser or music player, or it could be an operating system thread, but it is one task. Not two or more. Never zero, either. One. Always.

This sounds like trouble. For what if, say, your music player hogs the CPU and doesn’t let any other tasks run? You would not be able to open a tool to kill it, and even mouse clicks would be futile as the OS wouldn’t process them. You could be stuck blaring “What does the fox say?” and incite a workplace riot.

That’s where interrupts come in. Much as the nervous system interrupts the brain to bring in external stimuli - a loud noise, a touch on the shoulder - the chipset in a computer’s motherboard interrupts the CPU to deliver news of outside events - key presses, the arrival of network packets, the completion of a hard drive read, and so on. Hardware peripherals, the interrupt controller on the motherboard, and the CPU itself all work together to implement these interruptions, called interrupts for short.

Interrupts are also essential in tracking that which we hold dearest: time. During the boot process the kernel programs a hardware timer to issue timer interrupts at a periodic interval, for example every 10 milliseconds. When the timer goes off, the kernel gets a shot at the CPU to update system statistics and take stock of things: has the current program been running for too long? Has a TCP timeout expired? Interrupts give the kernel a chance to both ponder these questions and take appropriate actions. It’s as if you set periodic alarms throughout the day and used them as checkpoints: should I be doing what I’m doing right now? Is there anything more pressing? One day you find ten years have got behind you.

These periodic hijackings of the CPU by the kernel are called ticks, so interrupts quite literally make your OS tick. But there’s more: interrupts are also used to handle some software events like integer overflows and page faults, which involve no external hardware. Interrupts are the most frequent and crucial entry point into the OS kernel. They’re not some oddity for the EE people to worry about, they’re the mechanism whereby your OS runs.

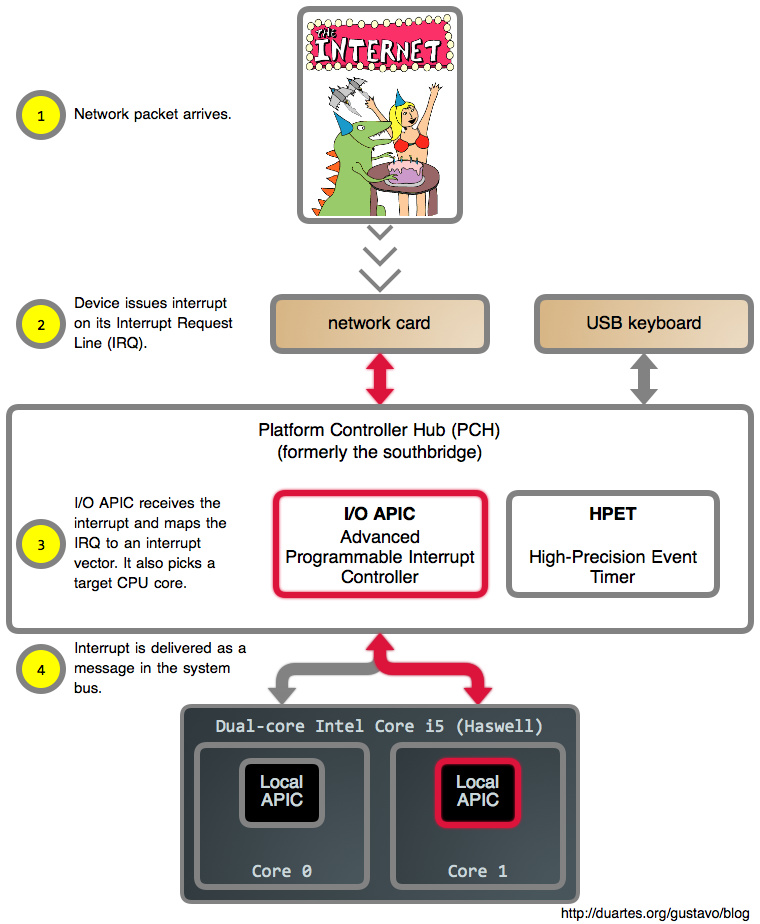

Enough talk, let’s see some action. Below is a network card interrupt in an Intel Core i5 system. The diagrams now have image maps, so you can click on juicy bits for more information. For example, each device links to its Linux driver.

Let’s take a look at this. First off, since there are many sources of interrupts, it wouldn’t be very helpful if the hardware simply told the CPU “hey, something happened!” and left it at that. The suspense would be unbearable. So each device is assigned an interrupt request line, or IRQ, during power up. These IRQs are in turn mapped into interrupt vectors, a number between 0 and 255, by the interrupt controller. By the time an interrupt reaches the CPU it has a nice, well-defined number insulated from the vagaries of hardware.

The CPU in turn has a pointer to what’s essentially an array of 255 functions, supplied by the kernel, where each function is the handler for that particular interrupt vector. We’ll look at this array, the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT), in more detail later on.

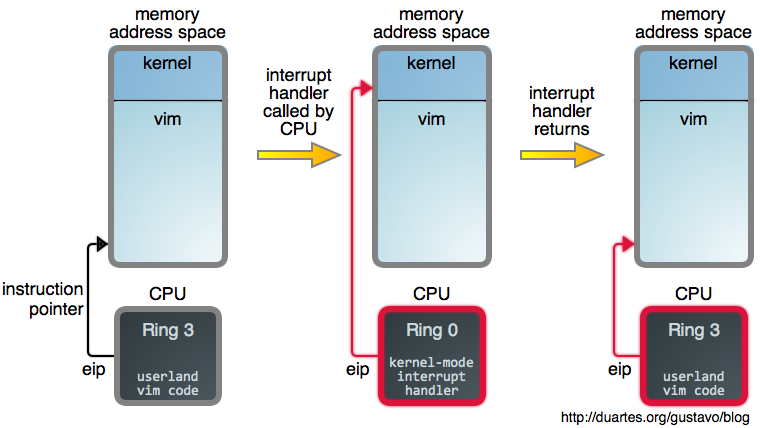

Whenever an interrupt arrives, the CPU uses its vector as an index into the IDT and runs the appropriate handler. This happens as a special function call that takes place in the context of the currently running task, allowing the OS to respond to external events quickly and with minimal overhead. So web servers out there indirectly call a function in your CPU when they send you data, which is either pretty cool or terrifying. Below we show a situation where a CPU is busy running a Vim command when an interrupt arrives:

Notice how the interrupt’s arrival causes a switch to kernel mode and ring zero but it does not change the active task. It’s as if Vim made a magic function call straight into the kernel, but Vim is still there, its address space intact, waiting for that call to return.

Exciting stuff! Alas, I need to keep this post-sized, so let’s finish up for now. I understand we have not answered the opening question and have in fact opened up new questions, but you now suspect ticks were taking place while you read that sentence. We’ll find the answers as we flesh out our model of dynamic OS behavior, and the browser scenario will become clear. If you have questions, especially as the posts come out, fire away and I’ll try to answer them in the posts themselves or as comments. Next installment is tomorrow on RSS and Twitter.

Comments