The last post in this series looks at closures, objects, and other creatures roaming beyond the stack. Much of what we’ll see is language neutral, but I’ll focus on JavaScript with a dash of C. Let’s start with a simple C program that reads a song and a band name and outputs them back to the user:

1 |

|

If you run this gem, here’s what you get (=> denotes program output):

1 | ./stackFolly |

Ayeee! Where did things go so wrong? (Said every C beginner, ever.)

It turns out that the contents of a function’s stack variables are only valid while the stack frame is active, that is, until the function returns. Upon return, the memory used by the stack frame is deemed free and liable to be overwritten in the next function call.

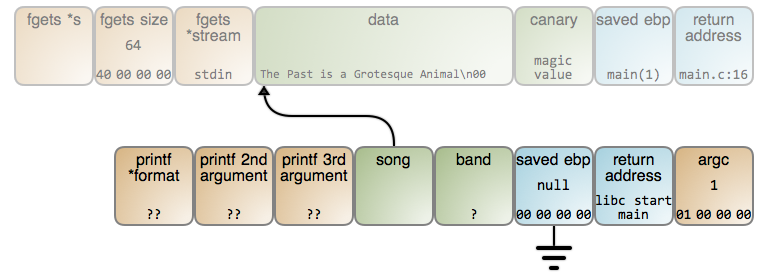

Below is exactly what happens in this case. The diagrams now have image maps,

so you can click on a piece of data to see the relevant gdb output (gdb commands

are here). As soon as read() is done with the song

name, the stack is thus:

At this point, the song variable actually points to the song name. Sadly, the

memory storing that string is ready to be reused by the stack frame of

whatever function is called next. In this case, read() is called again, with

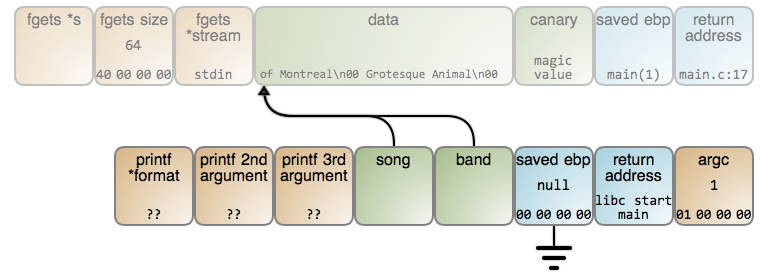

the same stack frame layout, so the result is this:

The band name is read into the same memory location and overwrites the

previously stored song name. band and song end up pointing to the exact

same spot. Finally, we didn’t even get “of Montreal” output correctly. Can you

guess why?

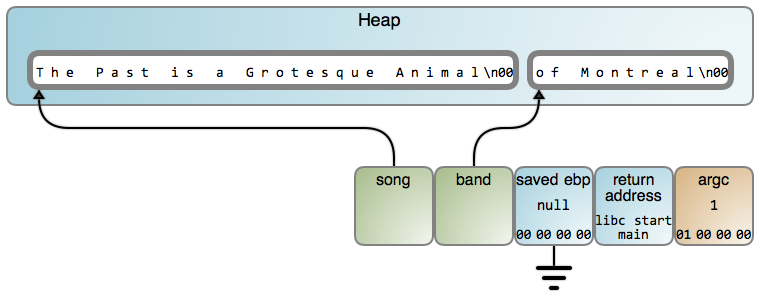

And so it happens that the stack, for all its usefulness, has this serious limitation. It cannot be used by a function to store data that needs to outlive the function’s execution. You must resort to the heap and say goodbye to the hot caches, deterministic instantaneous operations, and easily computed offsets. On the plus side, it works:

The price is you must now remember to free() memory or take a performance hit

on a garbage collector, which finds unused heap objects and frees them. That’s

the fundamental tradeoff between stack and heap: performance vs. flexibility.

Most languages’ virtual machines take a middle road that mirrors what

C programmers do. The stack is used for value types, things like integers,

floats and booleans. These are stored directly in local variables and object

fields as a sequence of bytes specifying a value (like argc above). In

contrast, heap inhabitants are reference types such as strings and

objects. Variables and fields contain a memory address that

references these objects, like song and band above.

Consider this JavaScript function:

1 | function fn() |

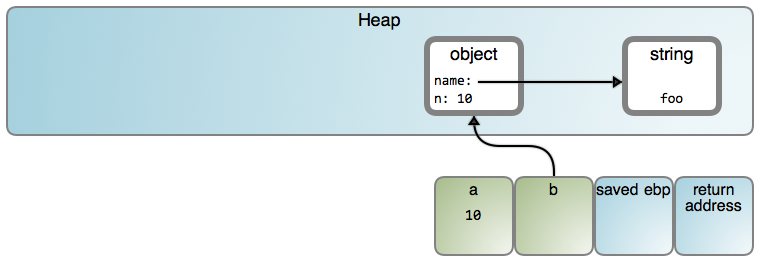

This might produce the following:

I say “might” because specific behaviors depend heavily on implementation. This post takes a V8-centric approach with many diagram shapes linking to relevant source code. In V8, only small integers are stored as values. Also, from now on I’ll show strings directly in objects to reduce visual noise, but keep in mind they exist separately in the heap, as shown above.

Now let’s take a look at closures, which are simple but get weirdly hyped up and mythologized. Take a trivial JS function:

1 | function add(a, b) |

This function defines a lexical scope, a happy little kingdom where the

names a, b, and c have precise meanings. They are the two parameters and

one local variable declared by the function. The program might use those same

names elsewhere, but within add that’s what they refer to. And while

lexical scope is a fancy term, it aligns well with our intuitive understanding:

after all, we can quite literally see the bloody thing, much as a lexer

does, as a textual block in the program’s source.

Having seen stack frames in action, it’s easy to imagine an implementation for

this name specificity. Within add, these names refer to stack locations

private to each running instance of the function. That’s in fact how it

often plays out in a VM.

So let’s nest two lexical scopes:

1 | function makeGreeter() |

That’s more interesting. Function hi is built at runtime within makeGreeter.

It has its own lexical scope, where name is an argument on the stack, but

visually it sure looks like it can access its parent’s lexical scope as well,

which it can. Let’s take advantage of that:

1 | function makeGreeter(greeting) |

A little strange, but pretty cool. There’s something about it though that

violates our intuition: greeting sure looks like a stack variable, the kind

that should be dead after makeGreeter() returns. And yet, since greet()

keeps working, something funny is going on. Enter the closure:

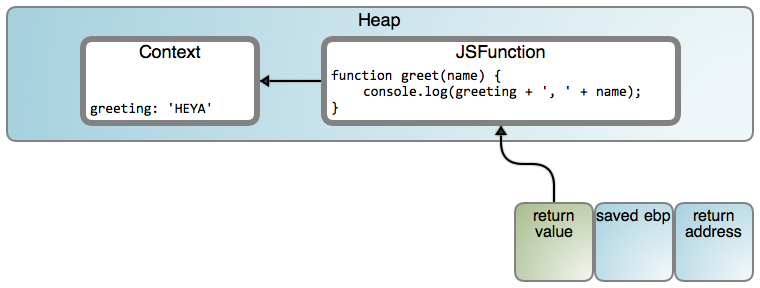

The VM allocated an object to store the parent variable used by the inner

greet(). It’s as if makeGreeter's lexical scope had been closed over at

that moment, crystallized into a heap object for as long as needed (in this case,

the lifetime of the returned function). Hence the name closure, which makes

a lot of sense when you see it that way. If more parent variables had been used

(or captured), the Context object would have more properties, one per

captured variable. Naturally, the code emitted for greet() knows to read

greeting from the Context object, rather than expect it on the stack.

Here’s a fuller example:

1 | function makeGreeter(greetings) |

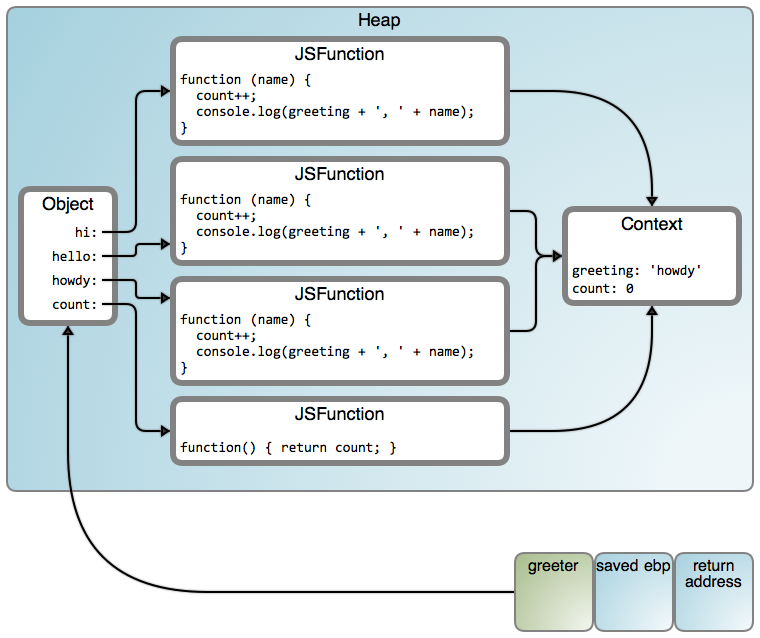

Well… count() works, but our greeter is stuck in howdy. Can you tell why?

What we’re doing with count is a clue: even though the lexical scope is closed

over into a heap object, the values taken by the variables (or object

properties) can still be changed. Here’s what we have:

There is one common context shared by all functions. That’s why count works.

But the greeting is also being shared, and it was set to the last value iterated

over, “howdy” in this case. That’s a pretty common error, and the easiest way to

avoid it is to introduce a function call to take the closed-over variable as an

argument. In CoffeeScript, the do command provides an easy way to

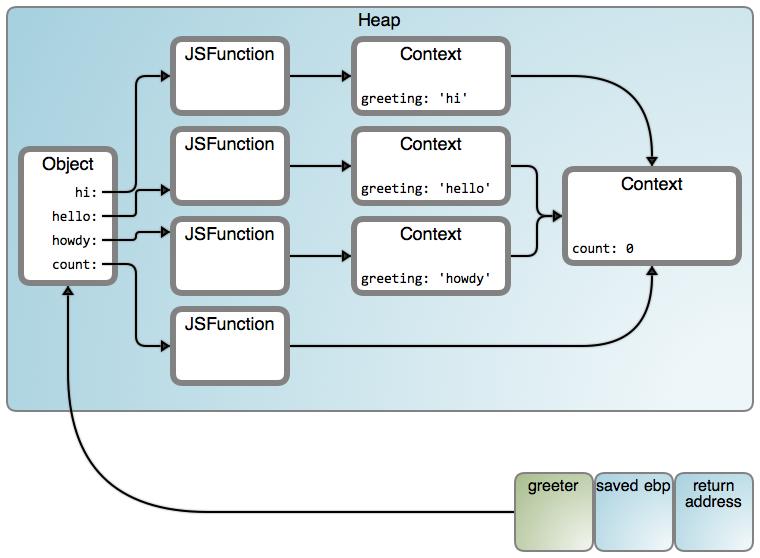

do so. Here’s a simple solution for our greeter:

1 | function makeGreeter(greetings) |

It now works, and the result becomes:

That’s a lot of arrows! But here’s the interesting feature: in our code, we closed over two nested lexical contexts, and sure enough we get two linked Context objects in the heap. You could nest and close over many lexical contexts, Russian-doll style, and you end up with essentially a linked list of all these Context objects.

Of course, just as you can implement TCP over carrier pigeons, there are many ways to implement these language features. For example, the ES6 spec defines lexical environments as consisting of an environment record (roughly, the local identifiers within a block) plus a link to an outer environment record, allowing the nesting we have seen. The logical rules are nailed by the spec (one hopes), but it’s up to the implementation to translate them into bits and bytes.

You can also inspect the assembly code produced by V8 for specific cases. Vyacheslav Egorov has great posts and explains this process along with V8 closure internals in detail. I’ve only started studying V8, so pointers and corrections are welcome. If you know C#, inspecting the IL code emitted for closures is enlightening - you will see the analog of V8 Contexts explicitly defined and instantiated.

Closures are powerful beasts. They provide a succinct way to hide information from a caller while sharing it among a set of functions. I love that they truly hide your data: unlike object fields, callers cannot access or even see closed-over variables. Keeps the interface cleaner and safer.

But they’re no silver bullet. Sometimes an object nut and a closure fanatic will argue endlessly about their relative merits. Like most tech discussions, it’s often more about ego than real tradeoffs. At any rate, this epic koan by Anton van Straaten settles the issue:

The venerable master Qc Na was walking with his student, Anton. Hoping to prompt the master into a discussion, Anton said “Master, I have heard that objects are a very good thing - is this true?” Qc Na looked pityingly at his student and replied, “Foolish pupil - objects are merely a poor man’s closures.”

Chastised, Anton took his leave from his master and returned to his cell, intent on studying closures. He carefully read the entire “Lambda: The Ultimate…” series of papers and its cousins, and implemented a small Scheme interpreter with a closure-based object system. He learned much, and looked forward to informing his master of his progress.

On his next walk with Qc Na, Anton attempted to impress his master by saying “Master, I have diligently studied the matter, and now understand that objects are truly a poor man’s closures.” Qc Na responded by hitting Anton with his stick, saying “When will you learn? Closures are a poor man’s object.” At that moment, Anton became enlightened.

And that closes our stack series. In the future I plan to cover other language implementation topics like object binding and vtables. But the call of the kernel is strong, so there’s an OS post coming out tomorrow. I invite you to subscribe and follow me.

Comments